While listening intently to Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall this week, a passage from the chapter Alas, What Shall I Do For Love? stood out in a way that I have not read or heard before. Thomas Cromwell is showing young Thomas Avery a book he has been sent - Brother Luca Pacioli’s Summa de Arithmetica, a book that tells the reader how to keep accounts. It is a beautiful object, ‘bound in deepest green with a tooled border of gold …. Its clasps are studded with blackish garnets’.

But it is not just a beautiful object. The contents are also beautiful. Cromwell believes this book contains ‘all the poems’ - accounts are not verse, but ‘anything that is precise is beautiful, anything that balances in all its parts, anything that is proportionate’. And so Thomas Avery goes on to keep Cromwell’s accounts, Pacioli’s book on his desk, guided by its advice. As Mantel goes on to tell us: ‘The page of an accounts book is there for your use, like a love poem. It’s not there for you to nod and then dismiss it; it’s there to open your heart to possibility’.

When Hans Holbein comes to paint Cromwell’s portrait, Mantel tells us that he takes Summa de Arithmetica from Thomas Avery’s desk and uses it as a prop - the beauty of the volume now recorded for posterity. It’s a wonderfully appropriate joke - and one that Mantel’s Cromwell would have enjoyed. This year, however, diligent researchers identified the book in Holbein’s painting as Cromwell’s Book of Hours, and realised that this object itself survives. Which is incredible - and opens up a whole new chapter about the real Cromwell.

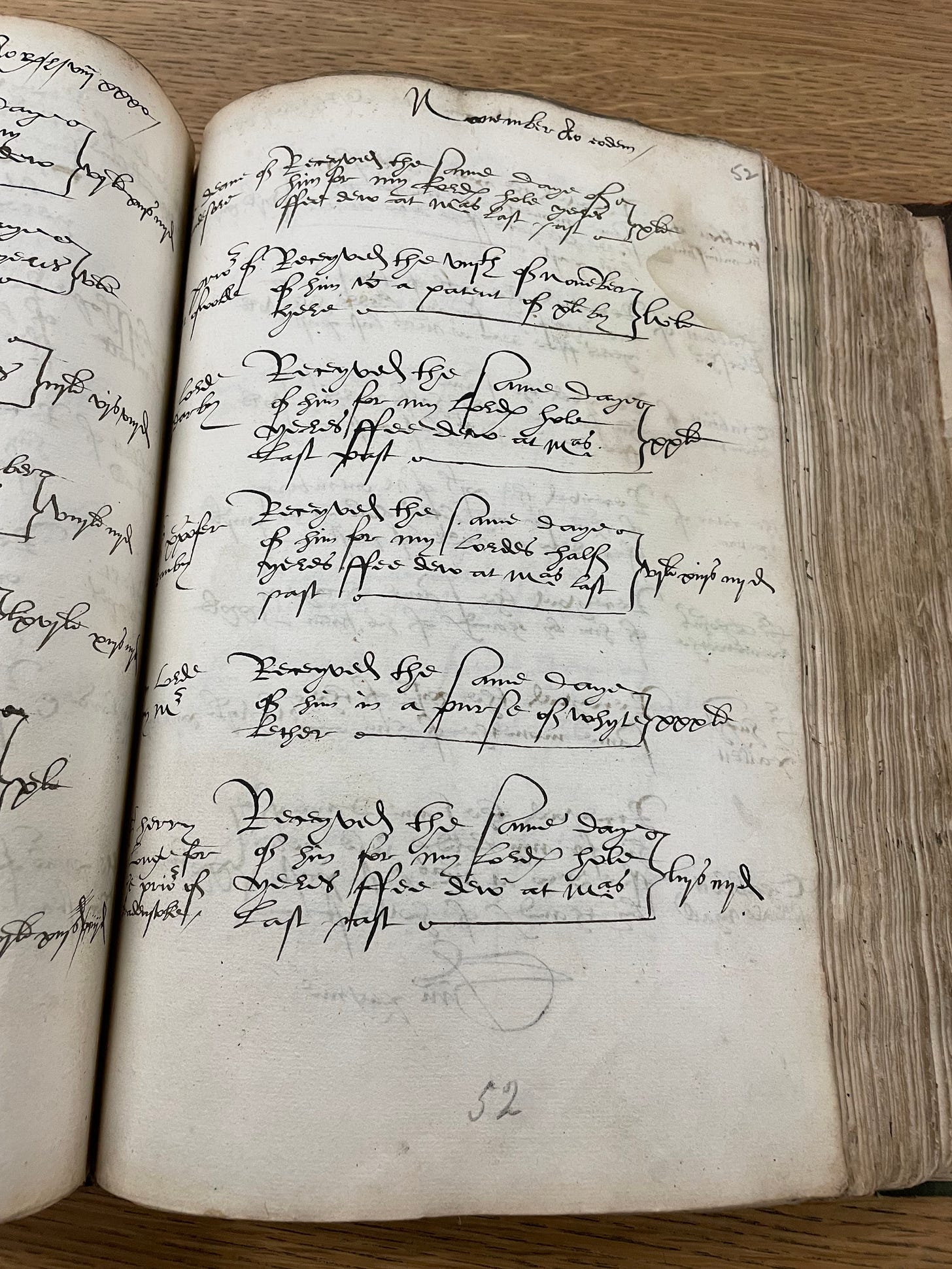

I haven’t yet seen Cromwell’s Hardouyn Hours, but I have seen another book that directly relates to these passages in Wolf Hall: Thomas Avery’s records of Lord Cromwell’s accounts, 1536-1539, the only volume that survives. I spent a happy time with them back in May. They are in Avery’ own hand. Towards the front, we see his signature, and the final page includes what looks like the signature of Gregory Cromwell.

I’m enormously privileged to live not far from the National Archives at Kew, and to be able to set aside a day a month to spend time among the papers of those that have long gone. My readings of - and creation of art related to - the Cromwell Trilogy are enriched by these visits, especially when I’ve actually seen a document or an object that is referenced. I suspect strongly that Avery’s book was one of those objects that opened Hilary’s ‘mind to possibility’ when she was preparing the Cromwell Trilogy. She certainly did not ‘nod and then dismiss it’. It was there for her use.

In My Studio

I should be in the studio right now, but it’s raining quite heavily and I am having an endometriosis flare so I’m still at home waiting to be able to walk over there - I’m keen to get on with a second motif to add to my Cromwell Trilogy Cloth. I decided to paint on calico this week - and it took a while to get the right paint and the right effect - there was some bleeding of inks and accompanying irritation - but after a couple of days’ work I ended up with two of Cromwell’s Cornish Choughs, ready to go onto the Cloth.

If in doubt, I always paint or draw or stitch a Cornish Chough. I have lots of them in different forms. I have sedate ones - representing those on Cardinal Wolsey’s Coat of Arms - and rough ones - representing those on Cromwell’s. The ruffians are more fun to create.

This week I produced three pairs of Choughs while I trying to get the right paint effect. I’m sure they will all come in useful one way or another. And I already know what the second Cromwell Trilogy Cloth motif will be…. Silver Bells.

What caught my eye?

I was looking at my photographs of Lord Cromwell’s account books alongside a summary that is available online through the index of Henry VIII’s Letters and Papers (sadly, my reading of Secretary Hand is not good enough to be able to read straight from Thomas Avery’s handwriting). And my eye was caught by an entry for 29 December 1538 when Thomas Cromwell paid 34 shillings and 6d for ‘bells for Anthony’s coat’.

And there, in The Mirror and the Light, those bells can be heard. In the autumn of 1536, Anthony the jester asks Cromwell ‘Sir, when was it heard of, that a man was fool to the Lord Privy Seal, and was not hung with silver bells?’ Cromwell tells Anthony to ‘tell Thomas Avery to give you a budget. Then you can buy your own bells.’ And we see him ringing them, walking through Austin Friars.

In July 1537, Cromwell paid the Hampton Court Gardener 20d for bringing him artichokes. I like the images that conjures in my mind. And it give me an idea for progressing another piece of work. More of that next week.

I love how you are so immersed in the world created so magnificently by Hilary Mantel.

I'm glad you brought this up. When I was listening to that Hans Holbein passage the other night, it occurred to me that it was a different book to the one they had recently discovered. Mantel does say Holbein rejects Cromwell's bible because it is too tattered and thumbed. A hint to his religiosity, so important to the book.