When Thomas Cromwell goes home to the Austin Friars in April 1527, his wife Lizzie is still up, even though it is one o’clock in the morning. “Forget where you lived?” she asks.

With these words, Hilary Mantel sets up the domestic life of Cromwell in Wolf Hall, creating an atmosphere that he, and the reader, seek to recapture at various points in the trilogy. Within two years, Cromwell is in crisis, and at two o’clock, and at three - in the middle of the small hours again - he knows that ‘he doesn’t need to think of going home; there’s no home to go to’.

I have been thinking about Cromwell’s homes a lot recently. Last week I visited a couple of them: Great Place at Stepney and Canonbury House. When I say I visited them, what I mean of course is that I went to see where they once were.

Nothing remains of the Stepney house, but with the assistance of the Tudor Travel Guide I think I managed to stand at the edge of Cromwell’s grounds.

And at Canonbury I saw the Tower that Cromwell once owned - or at least the Tower as it is today. It has been renovated and altered since 1540, but perhaps he would still recognise it. When I first read The Mirror and the Light I couldn’t imagine what it looked like - so I wanted to see where Call-Me eavesdropped on conversations, and Christophe climbed the stairs to warn of a storm. I hope to go inside in the not-too-distant future…

In My Studio

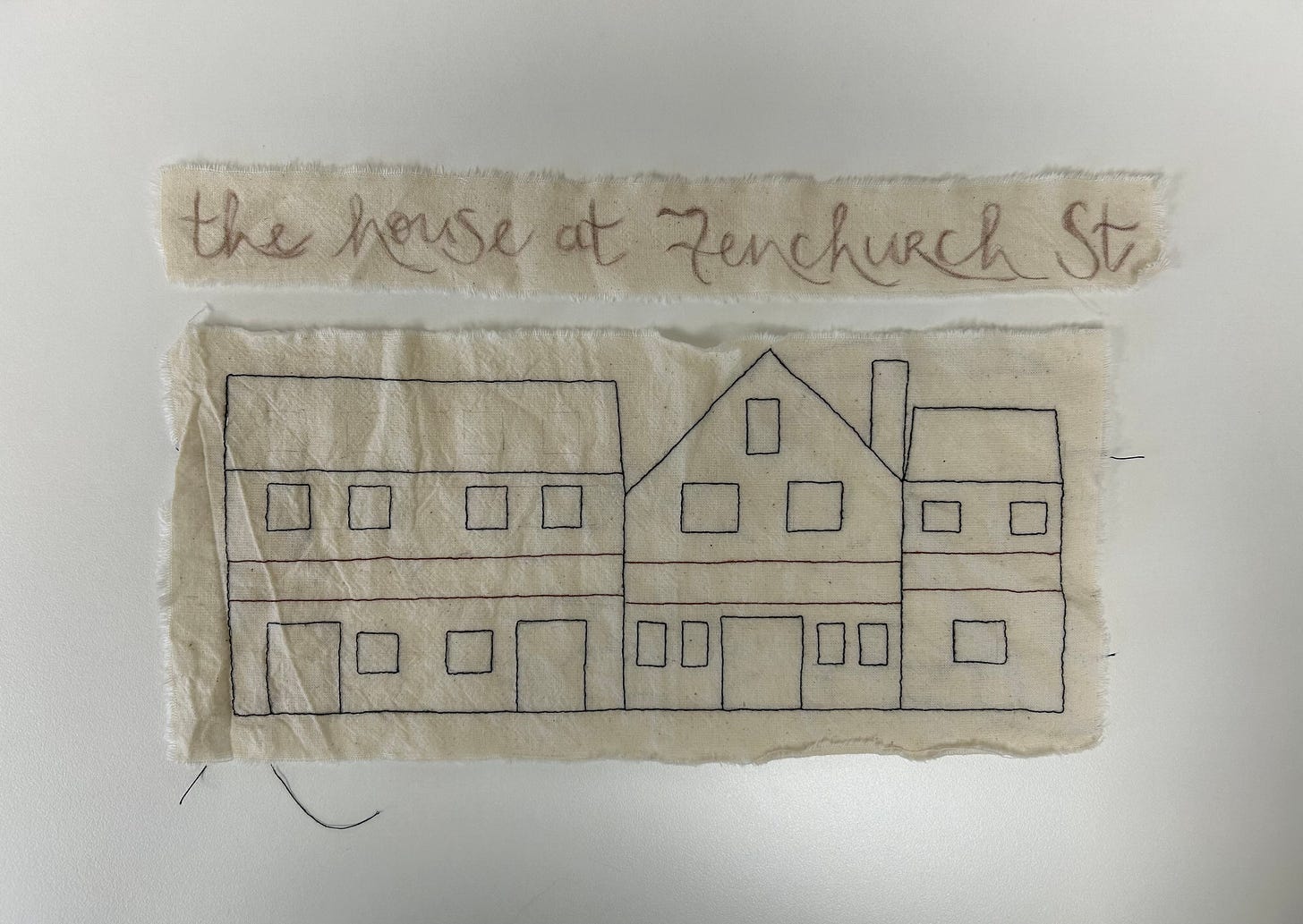

All this visiting has a purpose: over the last six weeks or so, I have been stitching Cromwell’s houses on a large scale. There are three in progress: the house at Fenchurch Street, which is almost complete, Austin Friars One, and Austin Friars Two - with Stepney and Canonbury (and other houses) to be added to the series. I wanted the house images to look quite flat, with text overlaying the buildings, like architectural plans that could be rolled together, but they just looked - well - flat. I was hoping that a bit of Cromwelling would help bring the project to life. And it seems to have done so - albeit not in the way I expected.

Yesterday, I restitched a much smaller Fenchurch Street house on a bit of scrap calico. Rather than focusing on the large architectural plans, I had the notion that had Cromwell indeed forgotten where he lived, he might need a little portable book to remind him of his various properties. And that small scale has worked much better.

But what to do with the original larger pieces - which stretch over metres of fabric?

Today, I put the large Fenchurch Street piece up on my design wall, noted that a couple of letters were not quite right, and resolved to restitch them. And then I looked at the whole piece, with a hard Cromwellian stare, and admitted to myself that it doesn’t work at all.*

I tried for a minute to convince myself that I could argue that the flatness was a response to Cromwell having ‘no home to go to’. But I knew that this rationalisation was entirely false.

So. The stitching must be unpicked and the fabric reused - and the unravelled thread might be rescuable if I am careful.

I have to put aside the knowledge that this represents weeks of work, and reframe it as development time. I think the concept for the Cromwell Houses piece is sound - but the initial execution isn’t. But working on a smaller scale presents new possibilities, a different form perhaps. And it feels like I have had a breakthrough.

*It doesn’t work to the extent that I photographed it to include in this piece and I am not going to share it. And it won’t matter what I do to it, it isn’t salvageable.

What caught my eye?

I’m going through summaries of the State Papers of Henry VIII at the moment and it’s fascinating to see so many textile references in amongst records of diplomatic correspondence and accounts of religious and political differences. I’d love to know more about one Thomas Foster, the King’s “broderer” who, in 1512, was paid for embroidered horse harnesses and two “pendante trappers of russet satin”. I’m waiting for him and other “broderers” to appear in later papers.