“If I follow the river is that as good as anything?”

I continue to stitch on my Cromwell Narrative Cloth, and it continues to make slow but steady progress. While it develops, I will be posting some reflections about my earlier Cromwell Trilogy stitchery. This is the second in a series of posts about my first Wolf Hall Quilt, made between 2020 and 2021. It’s a textile piece that comes with a very strong sense of time and place, and the restrictive circumstances in which it was made had a significant impact on the finished work, which only became apparent after it was complete. This post follows on from last week’s post about how I started stitching Wolf Hall during the Covid-19 Pandemic.

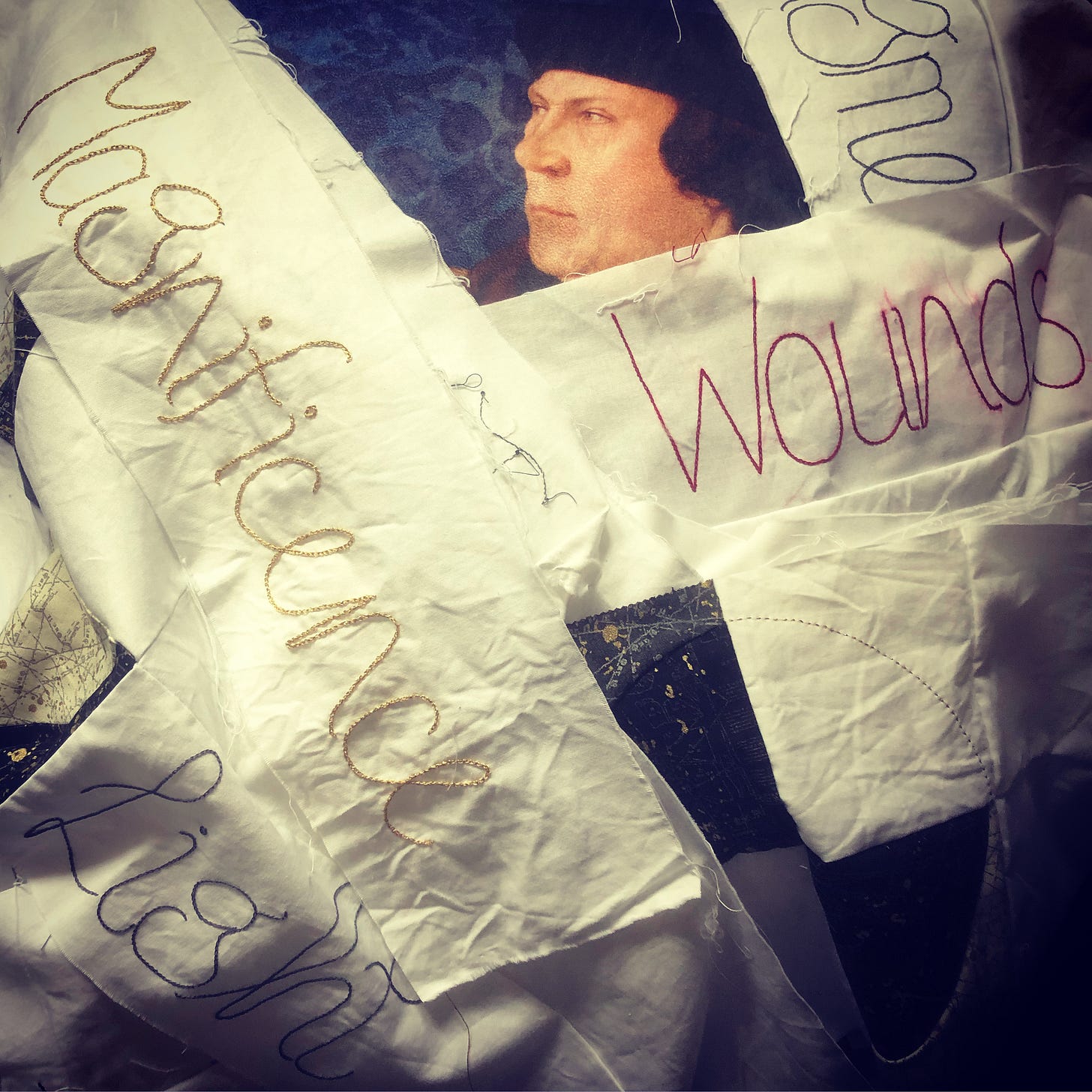

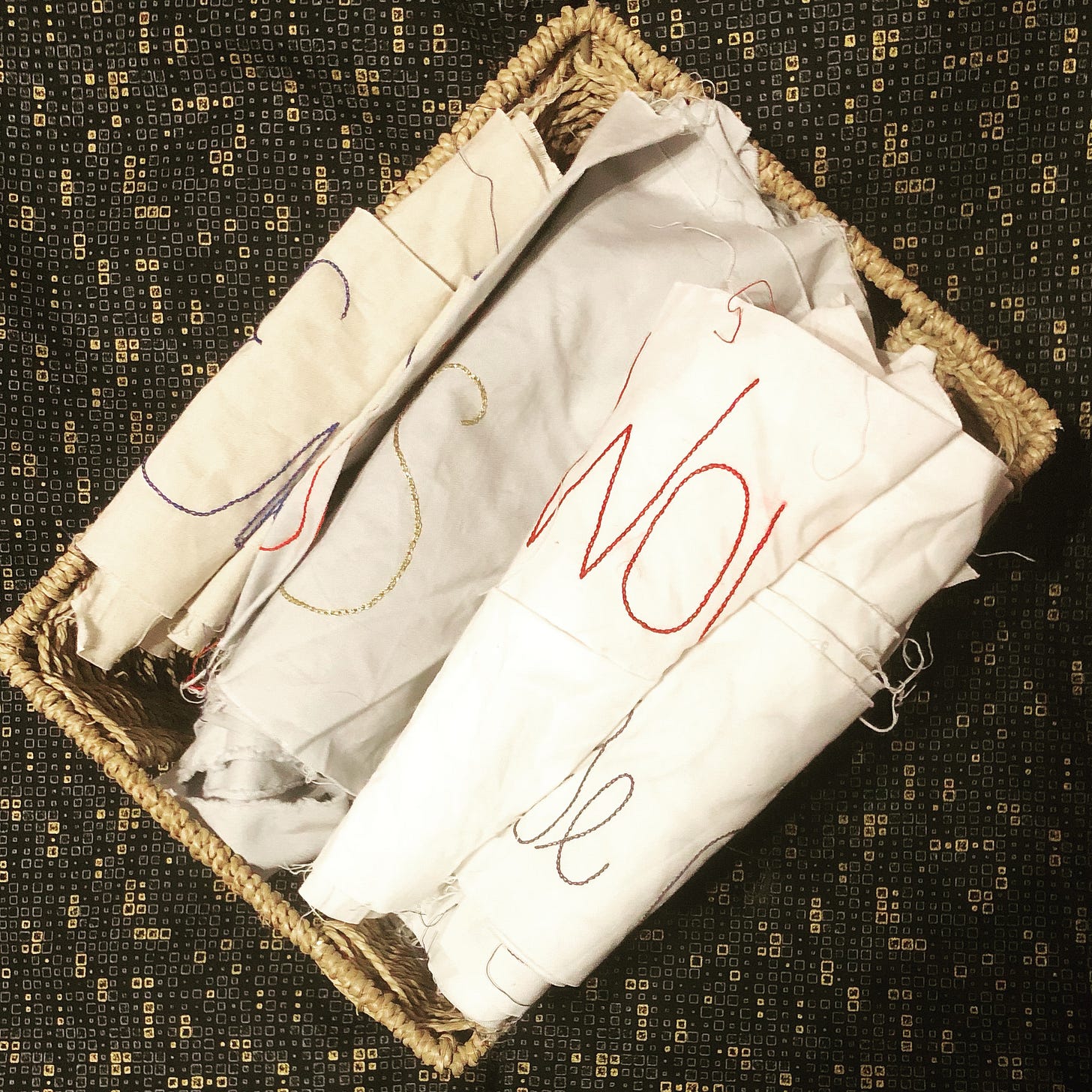

By the end of 2020, I had a whole set of stitched chapter titles for the whole of Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell Trilogy. They were all chain stitched, in various threads - red, brown, gold, black. All the colours chosen had a corresponding reference in the text (and I will write more about the use of colour in the first Wolf Hall Quilt in coming weeks). The chapter titles were everywhere, hanging from bookshelves, lurking on the couch, and finally, rolled up in a basket.

There was no plan for these pieces, no overall design in my head. Or rather, I knew what they were for, just not how to turn them into a coherent whole. In late 2020, I was invited to participate in the first international conference about Hilary Mantel’s work, which was to be hosted in October 2021 by the Huntington in California, the home of Hilary’s literary archives. I was to speak about the act of stitching in the Cromwell Trilogy, and how it had inspired my own creative practice. Once I knew I would be speaking at that event, and that the stitched piece would therefore be made public, I contacted Hilary’s agent to check that it would be all right for me to continue with my sewn interpretation. To my surprise, four hours later, I had an enthusiastic and encouraging email response from Hilary herself, looking forward to hearing more about it.

It was time to take the rolled up chapter titles out of their basket and turn them into something else. I had been nursing a vague idea that I might make a traditionally shaped quilt based on The Mirror and the Light and spent a while sketching plans and trying to decide whether to place pieces regularly or to make them irregular, according to how I responded to the corresponding part of the book. But I was never quite satisfied with that plan. I kept thinking there was something inappropriate about a bed-shaped item based on the novel: how could one sleep under the story of an execution?

And then I remembered an interview with Hilary Mantel on 6 September 2020 at an event for the Women’s Prize for Fiction in which she said:

All the stories are borne along on the River Thames and the river has its deeps and its mysteries and although the book is pegged very firmly to the historical record there are still subterranean depths within the hearts of the people whom the record concerns and we swim around below the surface.

She also mentioned using a noticeboard when planning Wolf Hall, and this in turn reminded me of a piece I read in the 2013 RSC programme for Wolf Hall, introducing an interview with the actor Ben Miles who has played Cromwell in all three parts of the trilogy:

Miles has taken over an office behind the main rehearsal room and around the walls snakes an extensive timeline of events compiled from fine-combing the books.

(Matt Trueman, ‘Chasing the Dead’, Wolf Hall Theatre Programme, Royal Shakespeare Company, 2013.)*

I liked the idea of something long, snaking out like the river, in a long strip. I had visions of a deconstructed set of the novels, pages rearranged chronologically in a very long horizontal timeline. And so I started to think about working a quilt in the shape of a long strip. At that point, I didn’t know how long it would be. I had a vision of joining together multiple strips so that all three books would be represented in one long piece, starting and ending with So Now Get Up. Given that the Wolf Hall quilt alone ended up being 46 feet long, I have since revised this idea. Well, for this particular project in any case.

This river shape - about 12 inches deep by 46 feet wide - might lead one to question whether the Wolf Hall quilt is a quilt at all. It isn’t intended to fit on a bed or a cot. It’s not square. It isn’t going to keep anyone warm. But taking the very specific meaning of the word “quilt” to mean a three-layer textile piece, this piece is a quilt. While the Victoria and Albert Museum say that ‘a quilt usually means a bed cover’ their definition goes on to clarify that it is:

made by two layers of fabric with a layer of padding (wadding) in between, held together by lines of stitching. The stitches are usually based on a pattern or design.

(www.vam.ac.uk/articles/an-introduction-to-quilting-and-patchwork [accessed 27 September 2021].)

The Wolf Hall quilt has three layers: grey cotton-linen mix on the back; a wadding or batting in the middle; and cotton fabric on the top. It’s joined together using two specific stitches: a standard quilting stitch, a running stitch that pierces all three layers; and a chain stitch, which is an embroidery stitch that would usually go through just one layer as an embellishment. I used chain stitch in two ways: the chapter titles are embroidered chain stitch; but elsewhere various items and pieces of text have been quilted in chain stitch, going through all three layers.

While I restricted the stitch type, I didn’t restrict the thread: in fact, I was more adventurous than I ever had been before, guided by colour and effect rather than fibre. The thread is a mixture of cotton, polyester, rayon, silk, and metallic, and I gave myself quite a lot of leeway in not sticking to my usual stronger cotton quilting threads, as this wasn’t an item that would undergo heavy handling or need to be washed.

Fabric, stitch and thread were fairly easy to decide upon, but the choice of wadding was a different matter. Wadding has an impact on the look, the feel, the depth, and the drape of a finished quilt. Your choice may be driven by how you quilt: if you quilt by machine, a cotton wadding may be your first choice; if you quilt by hand, you may find cotton wadding very tough. If you want a tiny stitch, bamboo might handle quite well but your stitches may come out bigger than you intended. If you recreate heritage items, you wouldn’t want to use a synthetic.

I spent weeks deciding on wadding, changing my mind over and over, testing out samples. My priority was creating a flat surface without too much loft. I thought quite seriously about using cotton wadding; it’s flat, it feels ‘authentic’. It is also incredibly hard on the hands and wrists and, as I always stitch everything by hand, I never enjoy working with it. I thought about wool - to stay in keeping with the textiles that Cromwell knew - but wool can mean moths. I thought for a decadent hour or two about silk. Silk wadding is very expensive, albeit a delight to work with.

In the end, I decided on a very flat synthetic. I had mixed feeling about this: I worried about microfibres and reminded myself frequently I wasn’t planning to wash the Cromwell work. I also became distracted by it not being ‘true’ to the period, before realising this was a false consideration: I am not in the business of historical recreation. I may enjoy learning about the recreation of the Black Prince’s Jupon by the wonderful Tudor Tailor for example, but witnessing the makers’ experiments with quilting through wool padding made my wrists ache in sympathy. And yes, my wrists. This was going to be a big piece, and as a hand stitcher, I have an ever-present concern about the impact of materials on hands and wrists and elbows. I had to remind myself that I wasn’t attempting to recreate the haptic experience of sewing in the Sixteenth Century. I was sewing some personal responses to a work written in the Twenty-First. And I felt that Cromwell probably wouldn’t mind a synthetic wadding. He might be interested in it as an innovation in the textile trade. Later, he took a different view once I started working with yellow satin. By then, nothing would do but silk wadding.

In my studio

Last week I joined more of the Cromwell Narrative Cloth together and was slightly taken aback by its weight. This time I am not using a light synthetic wadding but a silk/bamboo mix, which handles beautifully but is heavy. As I felt the heft of ten feet of the work I started to worry. This is going to really be bad for my hands. Is my shoulder acting up because of a bad pillow, or is it the weight of Thomas Cromwell? This is a really bad idea….

But I should have referred to my source text. The answer was there all the time. There is a passage in The Mirror and the Light in which Cromwell divides his life into seven distinct parts. And suddenly, my overwhelm was gone. Back to my chronological table, and a further breakdown into the seven lives of Cromwell, and I have seven Cromwell Narrative Cloths. I should have known that the solution would be in Hilary’s words.

So all the pieces are drawn up for Cromwell’s second life now - that’s where the Trilogy starts - and I am currently stitching in a snake that’s been picked up. I hope to be able to share this section in the next couple of weeks or so, although photographing it will be tricky!

What caught my eye?

My other work took me to a building near the Strand in London last week, and I noticed that I was on the site of the long gone Bishop’s palace of Durham House, where Katherine of Aragon lived after the death of her first husband, Prince Arthur. It’s not far from York Place - the site of Wolsey’s Palace, still marked by the street name. Many street names of the alleyways and side roads by the Thames still remember the old houses and palaces that once lined the river.

I mentioned last week that I visited Hampton Court Palace in early February. While I was there, I read a scene from Wolf Hall in the Great Hall; that of the play The Cardinal’s Descent into Hell. I didn’t post it last week, as I didn’t want to create spoilers for anyone who is participating in the slow read of the Cromwell Trilogy with the splendid

- so here it is.Reading this scene in the place in which it was set was an amazing experience. But when I got home I did some digging to satisfy both my and Simon’s curiosity and found that there is absolutely no evidence that this play (which did exist in some form, but does not survive) was ever performed at Hampton Court. But as any historian knows, absence of evidence is not evidence. And as a novelist, Hilary Mantel was free to use her imagination to fill in the gap in the historical record and set a memorable - not to mention deeply significant - scene in a place that still survives today.

*I have just realised that this piece from the RSC Wolf Hall programme has continued to haunt me and that somewhere in my mind it must have been the starting point for my current work, The Cromwell Trilogy Cloth, which stitches the events of the Trilogy in chronological order. I am slightly shocked that I have only fully understood this connection while writing this piece today…

And that’s the value of writing up this previous work. I am seeing all sorts of connections. I always say that the Wolf Hall Quilt isn’t satisfactory as a piece of textile art, but it is a jumping off point for further projects it’s been really valuable.