Back in November I was asked whether I was interested in Thomas Cromwell before reading Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. This inspired me to write a couple of posts about how I came to research and stitch Cromwell so intensively.

The first piece about my early experience of reading historical fiction can be found in the previous post. And this second part considers depictions of Cromwell as a Very Bad Man from three authors I read voraciously when growing up - Margaret Campbell Barnes, Jean Plaidy, and Maureen Peters. None were new writers when I was reading them (1980 or thereabouts) but their books were widely available from public libraries, which is where I found them.

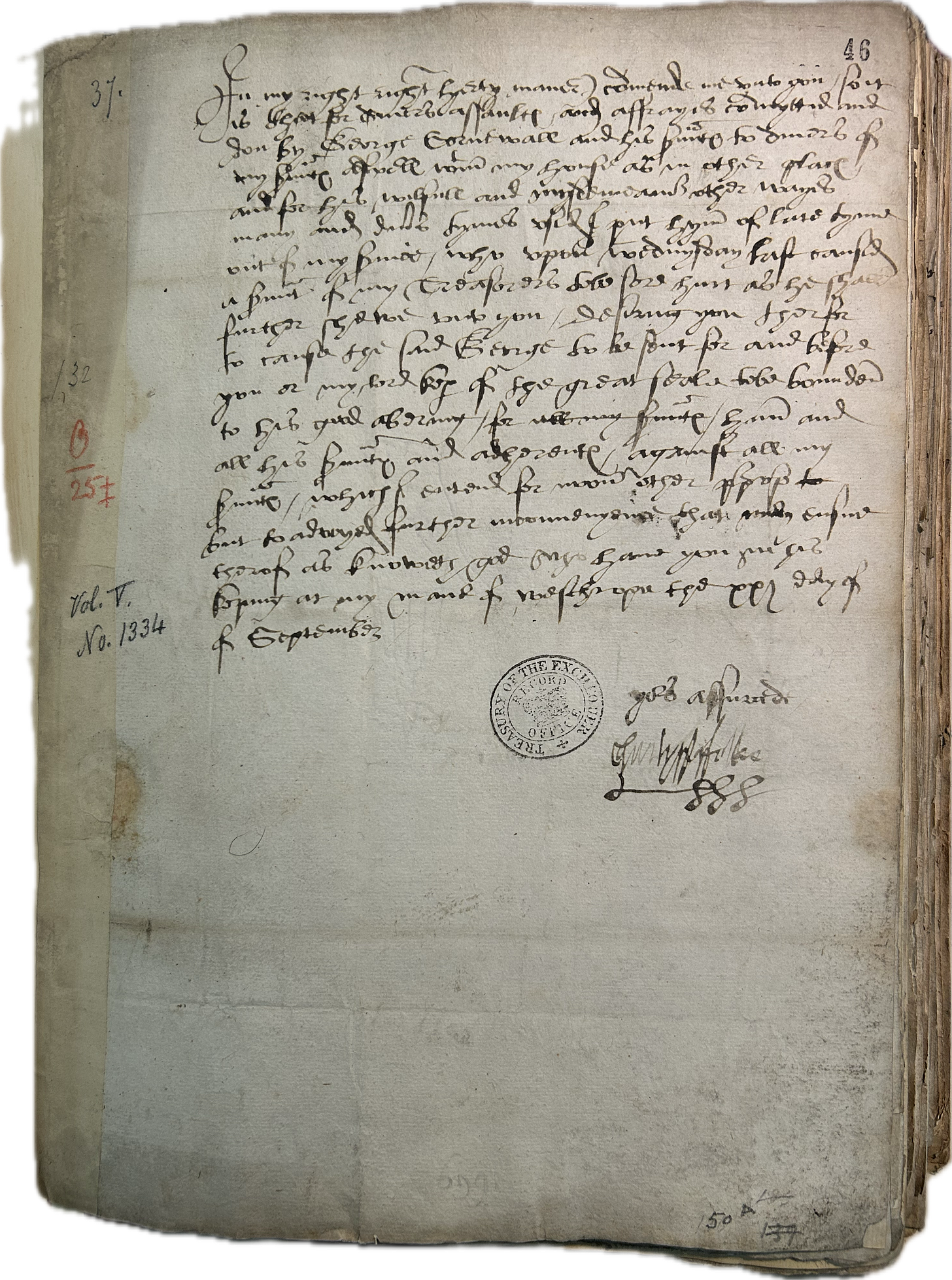

I have been meaning to write this post for some weeks now. But I was repeatedly unwell in December, and everything stood still until suddenly it was January. Yesterday, I sat in the Archives, looking up letters sent to Thomas Cromwell in 1532, and it seemed a good moment to ask myself why. Why am I doing this?

When Wolf Hall was published in 2009, aspects of my world view turned upside down. I was working as a governance advisor in the large charity sector at the time, and I immediately felt an affinity with Hilary Mantel’s version of Cromwell - his recognition of the importance of record keeping, of minutes; account books and inventories. I gave a copy of the novel to my then assistant, describing Cromwell as the ‘Patron Saint of Governance’. But Cromwell as protagonist - even, perhaps, hero - was not the Cromwell I thought I knew.

Yes, I did know of Cromwell before Hilary Mantel’s writing. He was a Very Bad Man Indeed and he got his just deserts. How did I come across him? In the previous How I met the Past post, I mentioned my love of Stalybridge Library, and it was there that I first met Cromwell.

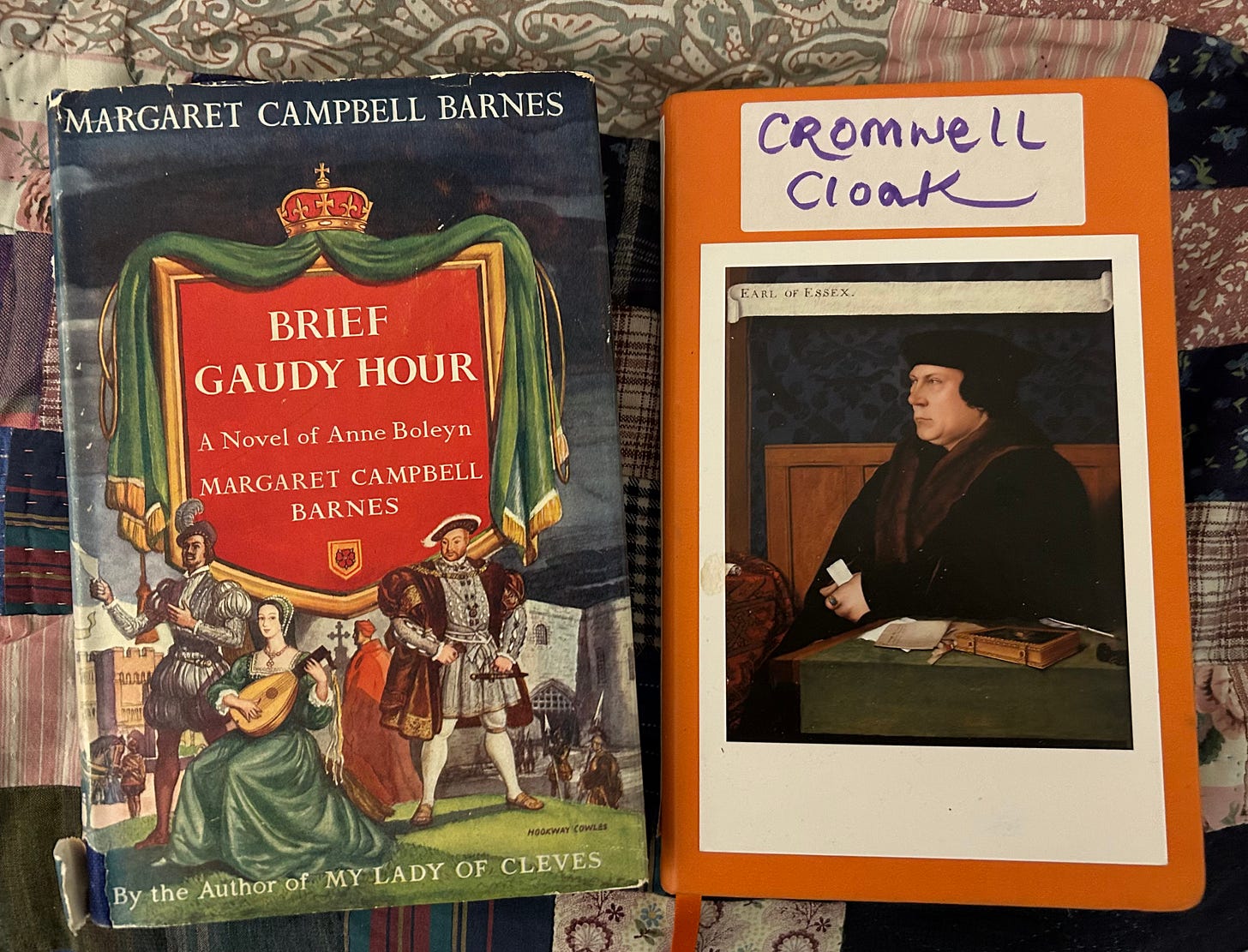

I was never shy of going into the Grown Up part of the library, and I can recall going to look at the historical novels of Margaret Campbell Barnes, largely because I loved the dustjackets. I can’t recall now how I first came across them, but I do know that I spent about a year taking the books from the shelves and looking longingly at the covers, before deciding, when I was about ten, that I was now old enough to get one out. I remember vividly taking Mary of Carisbrooke (1956) home with me - and devouring it. It was the story of the imprisonment of Charles I on the Isle of Wight, and his attempts to escape, aided by a young laundress called Mary Floyd. I was very taken by the idea that there was actually a laundress who worked at Carisbrooke Castle in the 1640s called Mary - indeed last year I discovered that there’s a reference to her in the Castle Museum even now. That book had such an impact that decades later, when my partner mentioned that he might like to visit the Isle of Wight, I jumped at the chance. I wanted to see Carisbrooke. We now go to stay on the Island twice a year, and have been doing so for years. It’s my favourite place.

That may seem to have little to do with Thomas Cromwell - although of course Mary of Carisbrooke is concerned with the actions of his great, great grand-nephew Oliver - but Barnes also wrote a novel about Anne Boleyn called Brief Gaudy Hour (1949) and I suspect that this was my first introduction to Thomas Cromwell. In this version of her story, Anne’s focus is on her thwarted relationship with Harry Percy, and her desire to take revenge on Wolsey - who I considered an absolute villain. Cromwell, as Wolsey’s ‘bullet-headed secretary’, ‘daily pushing his ugly feet more firmly into his dead master’s shoes’ is very much a secondary character. He grows in power in the background; there - but not terribly noticeably there. He’s Anne’s enemy, working to bring about her downfall behind the scenes; we don’t really see what he’s doing, but we hear about it afterwards, most notably when he invites Mark Smeaton to his house at Stepney, and forces a confession. As an adult re-reader, I notice a sense of innocence in Barnes’ writing, which means that she tends to keep unpleasant scenes at arm’s length. We hear about them via a character who recounts events, but we don’t ‘see’ them.

Not long after I discovered Barnes, I started reading Jean Plaidy. I had in fact had an early introduction to her at primary school, as she wrote a couple of books for children about the young Elizabeth and the young Mary Queen of Scots. I loved these when I was eight - although I don’t know what I would think of them now. As far as her novels for adults are concerned, I find her prose style somewhat heavy these days, and I don’t tend to re-read her. However, there’s no doubt in my mind that reading her when I was young helped develop my interest in history - albeit a very narrow version of history. As a young teenager I read Plaidy’s historical fiction avidly. I read her trilogy about Katherine of Aragon again and again, and became more and more aware of Cromwell, who made his presence felt in The King’s Secret Matter (1962). He was the mysterious lawyer called into Wolsey’s service, loyal to Wolsey up to a point, but only up to a point:

The lawyer walked from the apartment at the side of the Cardinal, his manner obsequious. He was thinking that Wolsey was growing old and that old men lost their shrewdness. Then his problem was pressing down upon him: What will Cromwell do when Wolsey has fallen? When would be the time for the parasite to leave his host? And where would he find another? Cromwell’s eyes glinted at the thought. He would leap up, not down. Was it such a long jump from a Cardinal to a King?

Plaidy’s Cromwell is driven by ambition, he is cunning, and intelligent, but rough. In Murder Most Royal (1949), the story of Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard, he is ‘of the people, just as Wolsey had been, but with a difference. Cromwell bore the marks of his origin and could not escape from them’. The King doesn’t like him, but recognises his usefulness, his ruthlessness, his lack of scruples. Not surprisingly, Cromwell’s motto is ‘The King is always right’ and Plaidy conjures a picture of an extremely unpleasant individual. When he invites Mark Smeaton to his house at Stepney, Smeaton is unsettled by the silence of his house, and wonders if Cromwell’s invitation is in fact friendly:

He was a crude man; he had never cultivated court graces, nor did he care that some might criticise his manners. The Queen might dislike him, turning her face from him fastidiously; he cared not a jot. The King might shout at him, call him rogue and knave to his face; still Thomas Cromwell cared not. Words never hurt him. All he cared was that he might keep his position in the realm, that he might keep his head safely in the place where it was most natural for it to be.

And Smeaton is right to be suspicious. Plaidy writes vividly - and terrifyingly - of his interrogation at Cromwell’s hands; and it’s an incredibly powerful, memorable scene. Indeed, it’s one that has stayed with me since I first read it back in 1980 - and it still has the power to horrify.

Plaidy begins with a P, and in Stalybridge Library, it didn’t take me long to discover another historical novelist whose books were almost next to hers: Maureen Peters. Unlike Plaidy and Barnes, Peters’ books are no longer in print, but I own a couple of lurid 1970s paperback editions. The first is Princess of Desire (1973), which was my favourite - all about the beautiful Mary Rose Tudor and the dashing, handsome, brave, completely marvellous Charles Brandon, and how they risked all to marry. Oh my word, I was so in love with Charles Brandon when I was 11. I still have a massive soft spot for him, and I still get a little thrill when I touch one of his letters in the archives.1

The second is Anne, The Rose of Hever (1969), which I have just re-read after 40 years, in preparation for writing this post. I remembered that there was something - well, odd - about Anne, The Rose of Hever but I couldn’t remember what it was.

Well, it’s Thomas Cromwell. In Peters’ telling, Cromwell is not only a Very Bad Man Indeed, but a Very Bad Man who is involved with occult practices. On the face of it, he’s everyone’s friend - including Anne’s (“Dear Master Cromwell!”) - but he has an unusual interest in religion. Not in religious reform - but in the Old Religion. He convinces Henry that a marriage with Anne according to the rites of the ‘Dianic Cult’ is the best way forward. Her lady in waiting has never attended a marriage ceremony before, but even so, she finds it strange:

The little room was bare of flowers or religious symbols, and parts of the ritual puzzled the girl. She had never heard that it was necessary for bride and bridegroom to cut their arms and mingle their blood, and the low chanting of the priest had a strange uneven quality that made her feel uncomfortable.

Cromwell tries to talk Harry Norris into poisoning Katherine of Aragon. And he convinces Henry that a fertility rite involving a blood sacrifice is necessary to appease the Old Gods of the countryside. It’s all very Wicker Man - and all very odd.

Due honour must be paid to the victim for her dying will nourish the strength of the king. She must be treated with respect because from her blood new fertility will enter the body of the monarch.

Right at the end of this rather bad book, once Cromwell has successfully arranged Anne’s trial and execution, he tells Francis Bryan, ‘I want you to ride to Wolf Hall’. Which takes us neatly back to Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell. Who also suggested a journey to Wolf Hall. But Hilary’s Cromwell would have been far better company. So that’s why I spend so much time researching and stitching him. He’s a worthy companion.

Hilary Mantel’s Charles Brandon - very different from the dashing hero of my girlhood - came as far more of a shock to me than the re-positioning of Cromwell himself, which I liked immediately. But I am reconciled to this unheroic Brandon, largely thanks to Nicholas Boulton’s immaculate performance in the RSC stage plays. Indeed, the “I would rob a house with you, Charles” exchange at the end of The Mirror and the Light between Boulton and Ben Miles, is one of my favourite memories of the productions. More recently, listening to The Rest is History podcast, I laughed rather more than was seemly on hearing Brandon being described as “an absolute lad” by Tom Holland.

Loved this, I knew little of Thomas Cromwell, other than a mostly poor reputation, and I became quickly enamored with him in reading the trilogy. I hadn’t read any other accounts of him that I recall, or he didn’t leave an impression in them. Charles Brandon the same. Loved hearing what you had read.

I enjoyed this so very much--I, too, was a library-loving young girl who was always coveting books which were meant for older patrons (checking out books written in German when I had yet to learn the language!). I had to laugh reading the bit about Cromwell trying to talk Norris into poisoning Katherine to appease the Old Gods--wow, SO odd.

Sharing the myriad 'versions' of Cromwell you've come across has given me a new outlook on some of the Wuthering Heights 'fan fiction' I've encountered and dismissed. While Heathcliff is entirely fictional, versions of him pop up in all manner of genre. I have always dismissed them; maybe it's time for me to read Wuthering Nights. No--I can't.